The goddesses of dawn tend to be associated with mirth, revelry, profligacy. This is not only true for the mostly equivalent Aurora and Eos, but also for the rather different Bast, and even the Japanese Ama-no-Uzume. This Aurora was painted by Fragonard in 1755 or 1756. It is about 131×95 cm in size, but I could not find out its location.

Vertumnus was a Roman garden god, probably of Etruscan origin, with no Greek equivalent. He could change his form at will. Pomona was a wood nymph, a goddess of fruitful abundance, she too without a Greek counterpart. Together they had a festival on August 13th, the Vertumnalia.

In book XIV of his Metamorphoses, Ovid tells the story how Vertumnus gained entry to Pomona’s orchard by disguising himself as an old woman. Then he seduced her by telling her the story of Anaxarete, who refused the advances of a shepherd named Iphis, remained unmoved even when he hanged himself on her doorpost and was turned into a stone statue for her cruelty.

The story of Vertumnus and Pomona thus gave an artist the opportunity to paint an old and a young woman together, if he wanted. Not all did. Those that did were remarkably often from the Netherlands, as in this case Caesar van Everdingen, who made another painting on the same subject later.

The Dionysos Cup

DIONYSOS, a pretty boy, was once captured by pirates, they wanted to enjoy his body, or sell him into slavery, or both. They tried to bind him, but no ropes would hold him, and he made vines grow out of the ship. Scared, they jumped into the water and were turned into dolphins.

There are many variants of this legend, I have restricted myself to the elements found on the famous Dionysos Cup by Exekias. It is a kylix, a flat bowl used for drinking wine (the English word “chalice” is derived from it), about 30cm in diameter. As the wine was drunk away, first the grapes and the dolphins would be uncovered, the ship with Dionysos on it only in the end.

The kylix is dated around 530 BC, a later work by Exekias. It was found in a tomb in Vulci in the mid-19th century and is now in the Staatliche Antikensammlungen in Munich.

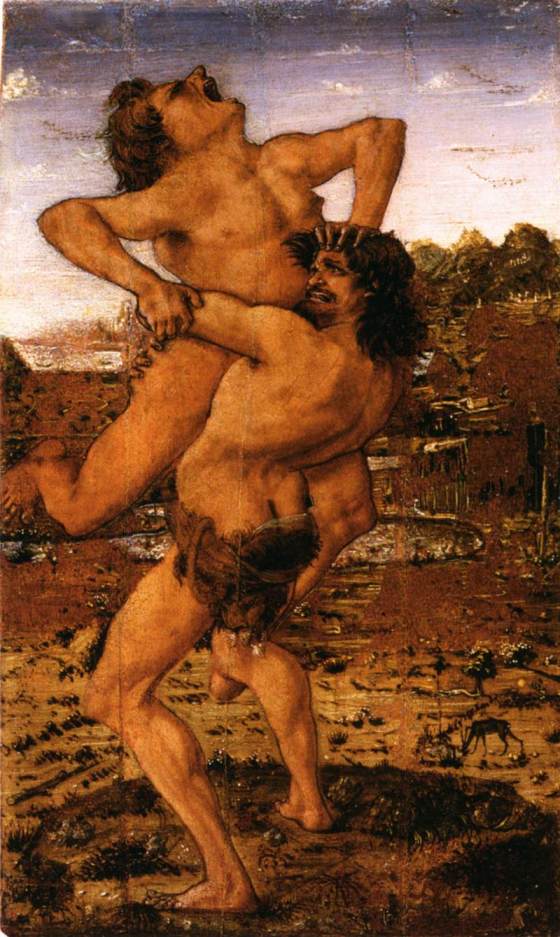

Antonio Pollaiuolo painted three small pictures of Heracles for Lorenzo il Magnifico, each about 17cm high. One of them seems to be lost, the other two are in the Uffizi. Vasari writes:

The first of these, which is slaying Antaeus, is a very beautiful figure, in which the strength of Hercules as he crushes the other is seen most vividly, for the muscles and nerves of that figure are all strained in the struggle to destroy Antaeus. The head of Hercules shows the gnashing of the teeth so well in harmony with the other parts, that even the toes of his feet are raised in the effort. Nor did he take less pains with Antaeus, who, crushed in the arms of Hercules, is seen sinking and losing all his strength, and giving up his breath through his open mouth.

Antaeus was the son of Poseidon and Gaia, invincible as long as his feet touched the ground. Heracles, on discovering his secret, lifted him up and crushed him in his arms.

Claude Gellée was born in the Duchy of Lorrain and is thus usually known as Claude Lorrain, but he lived and worked most of his life in Rome. He was far more a landscape than a history painter, he often hired other painters to add the figures and told his customers that he was selling them only the landscape, the figures were complimentary. As a landscape painter, he was often considered unmatched.

The subject of this 1645 painting is rather obscure, it has been done a few times, always as an excuse for a landscape: Apollo Guarding the Herds of Admetus and Mercury Stealing them. Apollo was once sentenced to a year of servitude to a mortal by the other gods, and he chose to become the herdsman of Admetus, King of Pherae in Thessaly, renowned for his hospitality and justice.

Where the side story of Mercury stealing the herds and later returning them (a drawing by Claude Lorrain of Mercury returning the herds was auctioned at Christie’s in 2003) comes from I have no idea. It seems to belong to the story of Apollo and Daphne rather, not to the Admetus story. At the time, mythology was maybe taken a bit too serious.

This is the only painting by Alexandre Charles Guillemot of which I could find a high-quality reproduction: Mars and Venus Surprised by Vulcan, 1827. Not a very convincing rendering of the story found in the fourth book of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, here in the translation of Garth and Dryden:

The Sun, the source of light, by beauty’s pow’r

Once am’rous grew; then hear the Sun’s amour.

Venus, and Mars, with his far-piercing eyes

This God first spy’d; this God first all things spies.

Stung at the sight, and swift on mischief bent,

To haughty Juno’s shapeless son he went:

The Goddess, and her God gallant betray’d,

And told the cuckold, where their pranks were play’d.

Poor Vulcan soon desir’d to hear no more,

He drop’d his hammer, and he shook all o’er:

Then courage takes, and full of vengeful ire

He heaves the bellows, and blows fierce the fire:

From liquid brass, tho’ sure, yet subtile snares

He forms, and next a wond’rous net prepares,

Drawn with such curious art, so nicely sly,

Unseen the mashes cheat the searching eye.

Not half so thin their webs the spiders weave,

Which the most wary, buzzing prey deceive.

These chains, obedient to the touch, he spread

In secret foldings o’er the conscious bed:

The conscious bed again was quickly prest

By the fond pair, in lawless raptures blest.

Mars wonder’d at his Cytherea’s charms,

More fast than ever lock’d within her arms.

While Vulcan th’ iv’ry doors unbarr’d with care,

Then call’d the Gods to view the sportive pair:

The Gods throng’d in, and saw in open day,

Where Mars, and beauty’s queen, all naked, lay.

O! shameful sight, if shameful that we name,

Which Gods with envy view’d, and could not blame;

But, for the pleasure, wish’d to bear the shame.

Each Deity, with laughter tir’d, departs,

Yet all still laugh’d at Vulcan in their hearts.

Boreas is the personification of the North wind, Oreithyia the daughter of the mythical King Erechtheus of Athens. He first tried to woo her, when that didn’t work, he abducted her. She bore him two daughters and two winged sons who joined the Argonauts.

Apart from this painting by Rubens (around 1615–20) and one by Evelyn de Morgan nearly four hundred years later, this myth has not made too much impact on newer art.

Danaë was the daughter of King Acrisius of Argos, whom an oracle had prophesied that he would be killed by his daughter’s son. To keep her childless, he locked her into a tower, but Zeus impregnated her in the shape of golden rain. The child was Perseus. Acrisius cast mother and son out to see in a wooden box, but they were saved and of course in the end the prophecy was fulfilled.

As early as Horace and Terence, authors have used the story as a metaphor for the power of gold, and most paintings of Danaë are thinly veiled bordello scenes. But there is another interpretation, found most prominently in the Fulgentius metaforalis, which describes her situation as thus:

Situ sublimata

Menibus vallata

Egestate sata

Agmine stipata

Prole fecundata

Auro violata

High up, walled in a tower, in great misery, surrounded by guards, pregnant, violated by gold she sits: chastity violated. Jan Gossaert (who signed as Joannes Malbodius from his place of birth, and is sometimes known as Jan Mabuse) seems to follow this interpretation in his 1527 painting, which is the oldest of this topic outside manuscripts. He not only emphasizes the tower situation most other artists ignore completely, he gives her a blue coat, the attribute of Mary.

Another remarkable thing about this painting is the similarity with the Danaë on a Boeotian red-figure crater from the classic era that the Louvre acquired in 1898. Jan Gossaert was the first Flemish painter to travel to Italy, maybe he saw a similar picture there. The Domus Aurea had already been discovered at the time, and the word grottesche had made its way into the Italian language.

Another remarkable thing about this painting is the similarity with the Danaë on a Boeotian red-figure crater from the classic era that the Louvre acquired in 1898. Jan Gossaert was the first Flemish painter to travel to Italy, maybe he saw a similar picture there. The Domus Aurea had already been discovered at the time, and the word grottesche had made its way into the Italian language.

Europa was a Phoenician princess, daughter of Agenor and Telephassa. Zeus approached her in the shape of a white bull as she was playing on the beach with her friends. The girls decorated the beautiful and apparently tame animal with flowers, and finally Europa climbed on his back. Now the bull suddenly took to the sea and swam with her to Crete, where he assumed human shape. She bore him three sons, Minos, Rhadamanthus, and Sarpedon. Later, she married Asterios, the king of Crete, and he adopted her sons.

Europa is the patron goddess of this blog. You will see her a lot.

The Rape of Europa is one of the classical topics of European art, dating back to at least the 7th century BC. This image is a detail from a painting by Nöel-Nicolas Coypel, who lived from 1690 to 1734 and was quite popular in his time. Among his surviving paintings are a Bath of Diana and a Birth of Venus, so maybe he liked painting people in or near water.

The Rape of Europa is one of the classical topics of European art, dating back to at least the 7th century BC. This image is a detail from a painting by Nöel-Nicolas Coypel, who lived from 1690 to 1734 and was quite popular in his time. Among his surviving paintings are a Bath of Diana and a Birth of Venus, so maybe he liked painting people in or near water.